Wing Chun is an incredibly practical, powerful martial art that’s been hijacked by brutes, geeks and frauds the world-over.

Its core concepts are overlooked out of ego by brutes, sidetracked out of fetish by geeks, and simply unrecognised by frauds.

Wing Chun usually has thorough technical grounding only because it’s bogged down by modern club/clan culture and unfortunately, associated enforced bad habits dampen its genuinity. I’ve just about mastered this art myself, so take my word for it. I’ve yet to see a self-described Wing Chun Kung Fu club teaching decent Turning Punches. They do one thing in the forms, inherited from genuinely impressive exponents of the art, and another thing in the short drills – passed down unwittingly for just a few generations. Yet you can’t go far wrong with Wing Chun’s practical Sticking Hands exercise – Chi Sau – so every clueless teacher is still able to make a good impression in the classroom and get people copying and reteaching his bad habits in conjunction with a portion of some real skill.

My best advice for Chi Sau (sticking hands) practitioners is: Less talk, more practice. I say this because the professing is rarely inline with the teacher’s actual action, and more to the point, his words are wrong but his Chi Sau is instinctive, natural and fine (except when he’s trying really hard to prove what he said, in which case his moves are disastrous and he will cover it up by preaching something trivial).

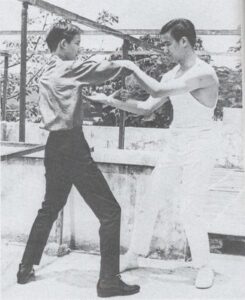

Nicknamed Hong Kong Street Fighting, Wing Chun has a huge reputation. It’s famed for being Bruce Lee’s main martial art before he founded Jeet Kune Do – before going to America to be the world’s highest paid movie star – and this tends to be used as the art’s main selling point. But in all honesty, speaking from experience, it’s not all good; Bruce would agree. Although Ip Chun – son of Yip Map (Bruce Lee’s Wing Chun teacher in Hong Kong) would sooner say Bruce left Wing Chun to avoid bringing trouble to the family; whether or not Bruce said this is significant no more than to tell us whether or not Bruce was polite and made up an excuse to avoid falling out with his former teacher. The bitter reality is, Yip Man’s Wing Chun had numerous fundamental problems. Modern day proponents of the art will argue Bruce didn’t understand it, couldn’t hack it, or wasn’t taught it in full, etc; but in reality, Bruce and I both found problems to the point where we have no choice but to stop saying “Wing Chun is my martial art”.

Now if you asked me what five things people are most likely to associate with Wing Chun, as a style, I’d say:

- Explosive – Short sharp energy bursts, bordering craziness when people are trying to train productively

- Angular – Lots of triangular structures and use of pivoting with strategic skeletal alignment – often a concept taken too far whereby people strike a silly pose and say it’s a Tan Sau, Bong Sau or Turning Punch – no, it’s actually a ridiculously off-balance expression of geekdom. The true move would be nowhere near so stretched or collapsed.

- Intensive – Rather than being a way of life, even though many travel annually to train in Hong Kong, Wing Chun tends to be a once-a-week or twice-a-week workout scheduled by its practitioners. On the right hour of the right week, they do endless quick repetitive movements as part of a rigourous little lob-sided Wing Chun workout.

- Teacher worship – Most Wing Chun students think their own teacher is the best fighter in the whole wide world, short of that really crazy guy who trains with him in Hong Kong once a year. To be fair, this is close to the truth of most martial arts, however, it’s especially excessive in Wing Chun. It usually also involves worshiping the teacher’s teacher; and the teacher’s teacher’s teacher; all the way to Yip Man, then it stops in a veil of unknowns where only the teacher recites the lineage right back to Ng Mui and Yim Wing Chun after looking it up online before the class.

- Practical – People say it’s the most practical, simple but sophisticated and scientifically-sound martial art in the world. When it’s done right, they may be close to the truth.

Handwork vs Footwork

Wing Chun’s hand techniques are generally so efficient – so simple yet sophisticated – that Wing Chun practitioners are rarely seen bending their knees properly and sitting down in a proper stance. When done right, the Wing Chun stance called Jeen Ma (arrow stance) or Biu Ma (pointed stance) is as defensively superior as a stance can get and perfectly complements the rest of the Wing Chun system as well as any other balanced style of martial art. Combined with the concept of Yiu Ma, but not so far that the concept of Sau Tai Sun is neglected – the Wing Chun stance can be quite dynamic in ranging from neutral to side-on positions but is always on the back leg – weighted backwards. Often taught leaning backwards without proper pelvis thrusting to verticalise the back after bending the knees, and without properly inward-turned toes or close enough knees, the Wing Chun stance is so often neglected because the hand techniques are simply so superior to that of other martial arts – largely thanks to the exercise of Chi Sau (Sticky Hands) which ensures students can quickly learn Wing Chun techniques and also ensures that teachers don’t easily forget much of what they’ve been taught.

Wing Chun’s hand techniques are so good that even the hand positions themselves become crooked with bad habits that go unnoticed because teachers are still able to impress their students even with bad habits included.

So what conclusions can we draw from this, and what lessons can we learn? I’d say we should turn to what really motivates us and purify that, then we can become more sensitive and aware of our own mistakes. Any remaining bad habits that go unnoticed will have little to fuel them and will soon fade away. This is the way of fighting without fighting and is the true foundation of every great style including Wing Chun.