China has a great, rich history spanning many thousands of years. The Chinese language is the oldest language on Earth, of all languages still widely used today – it dates back about 10,000 years, and the heritage of Chinese Kung Fu dates back about 2000 years.

Quite passive compared to their Japanese counterparts, but when they get their heads together, they make big things happen. For example, key inventions like Paper and the Compass come from China.

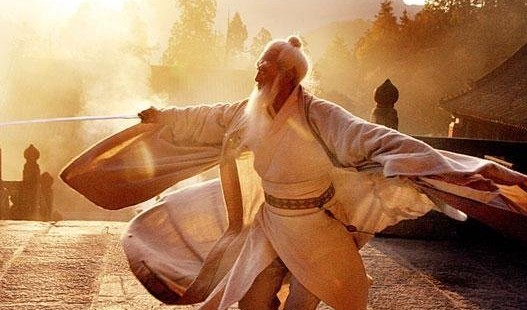

Chinese Kung Fu

Kung Fu traditionally refers to all Chinese martial arts – that is, all Oriental martial arts traditionally coming from China. However, Kung Fu literally means Hard Work, and as such, could arguably include any style of persistently practiced martial art in the world.

This site introduces you to a range of popular Chinese Kung Fu based martial arts including Tai Chi (Tai Ji Quan), Wing Chun (Yong Chun, Ving Tsun), Jeet Kune Do (Jie Quan Dao) and Shaolin (Siu Lum, Sil Lum).

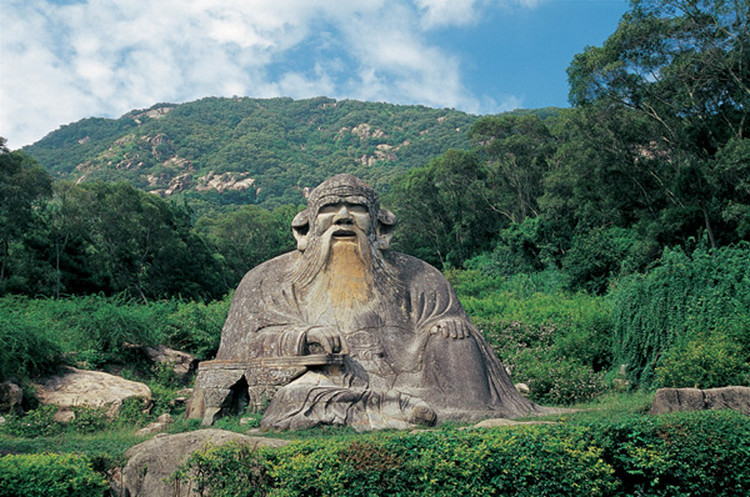

Unsurprisingly, Chinese Kung Fu varies in quality – from style to style and more importantly from teacher to teacher. But the Chinese Kung Fu community harbours pockets of outstanding skill – true excellence in the martial art, reminiscent of Bruce Lee who genuinely remained undefeated by all who challenged him. Sure, Japanese martial art has elements of excellence in its Aikido for example, and Capoeira has some cool moves not seen elsewhere which seem to flow smoothly and harmoniously, but the highest level of Chinese martial art is head and shoulders above its rivals. Chinese philosophy, is likewise, fully varied, but at its best, head and shoulders above anything else seen on Earth today. I’m talking about Laozi, not Confucius, and I’m talking about the original work, not the ill-translated material accessible to normal people today.

As smooth as Thai boxing may be, it’s not much less random than western kickboxing, where as Chinese Kung Fu is genuinely smart – when at its best – way beyond what other martial arts systems have accomplished.

The highest level of martial art, in theory, is the way of fighting without fighting, as momentarily captured on screen by Bruce Lee in Enter The Dragon. This matches the traditional Japanese theory of Tai Sabaki whereby it’s commonly taught in Aikido and Karate clubs alike that the best block is to move out of the way – avoid the conflict before any impact is made. This is the greatest style of martial art. You could say the spirit of this evasiveness is best embodied by Japanese Ninjutsu, but practical techniques are more refined by the Chinese (if you find the right teacher). Having said that, Ninjutsu is so loud and proud about evasiveness these days that a Tai Chi pracitioner is probably far better placed to evade a confrontation (by blending in with other people).

After fighting without fighting at all… The next greatest style of martial art – for when you can’t avoid the attack completely – is to blend with it. Become one with the opponent. This is a fundamental concept underlining the styles of both Chinese Tai Chi and Japanese Aikido.

The next greatest style of martial art – for when you have no emptiness and no oneness – is to maintain strength within the two dimentional scenario – the conflict – the impact – keeping strong structure – being immovable like a brick wall – hard as it may be, with well-pointed angular techniques and appropriate leverage, you can essentially use the force of the ground beneath you to help you stand strong like a brick wall – or bone wall for that matter (with skeletal alignment coming into play to save the day). This is seen in Shaolin at its best, and in Wing Chun Kung Fu quite regularly. Take Bruce Lee’s one-inch-punch for example – solid impact, with explosive fluidity behind it.

“Do” what?

Most Oriental martial arts make use of the word “Do” – this is the Cantonese, Japanese and Korean equivalent of the Mandarin word Dao. This highlights the impact of Daoist principles on Oriental martial arts and the general relevance of Daoist philosophy to creative culture in the Far East.

The Manchester Martial Arts Centre welcomes people from all backgrounds and all religions – we’re not a religious institution as such but the theory modules of our long-term courses are packed with inspiration from Daoist culture.

Here’s an excerpt from the Tai Ji Quan Jing:

There are so many other martial arts, full of differences on the surface.

But they all come down to the strong bullying the weak, and the fast beating the slow.

The strong beating the weak, and slow hands losing to fast hands.

This is all due to natural ability, it has nothing to do with skill.

The Tai Ji Quan Jing is the first of the Tai Chi Classics, but it doesn’t represent the greatest of Daoist scripture.

Let me now share with you something that may cause you to ask yourself a much deeper, more profound question. Here’s an excerpt from the Dao De Jing:

The more there’s rules, the poorer people get.

The sharper their weapons, the more they riot.

The more skilled their art, the more gross their work.

The longer the laws, the more there’s crime.So the wise man says:

I do nothing, and people change themselves.

I like peace, and people look after themselves.

I spread freedom, and people succeed.

I want nothing, and people get real.