Aikido is the most graceful Japanese martial art – it was created based on the pacifist beliefs of a master of Jujutsu called Morihei Ueshiba.

Aikido is the most graceful Japanese martial art – it was created based on the pacifist beliefs of a master of Jujutsu called Morihei Ueshiba.

Aikido works purely for self defence (not attack) because it depends on receiving committed on-coming force which it then utilises to perform a throw or standing takedown with minimal effort.

There are no clenched-fist strikes in traditional Aikido – all moves are open-handed. Many people supplement it with punches these days, for dealing with close-range problems, but this is not the way it was designed.

Many people take the system out of context and fail to make it work – these people do not really understand the purpose of Aikido.

Training usually begins with wrist-grab defences, and progresses to deal with lunging punches. Critics of the system will argue it doesn’t work against hesitant close-quarter grappling or close-range fast punching, and while this is usually true, Aikido’s tactics of distance management, agile footwork and constant evasive manoeuvres help you to avoid ever getting into those sticky close-quarter situations in the first place.

There is some training performed kneeling (in seiza position) and there is rolling to avoid injury upon being thrown; but Aikido is mostly a standing-up system.

Aikido focuses on maintaining good distance from an attacker, then absorbing and throwing their energy in circular motion (like a contracting then expanding spiral). It utilises perpetually moving agile footwork to manage distance before slipping & redirecting attacks with good timing.

Aikido offers a good skillset to have in dealing with multiple attackers in the streets who may or may not be carrying weapons, and may or may not seek revenge (immediately, or another day) for any overkill in case you cause any unnecessary injuries or death. In such scenarios you need to be very aware of distance and timing, stay on your feet and keep moving while having a commitment to not unnecessarily escalating the situation and having a continued desire to achieve the most peaceful resolution possible, for everyone’s benefit.

Fun Fact: The founder of Judo (Jigoro Kano), in his final years, was known to send some of his best students (eg Minoru Mochizuki) to learn Aiki-Jujutsu from Morihei Ueshiba (Aikido’s founder) prior to the establishment of the even more balanced & graceful system of Aikido.

Aikido is also a delicate system of spiritual physical exercise (like Tai Chi or Yoga) — so much so, that its holistic health benefits are just as significant as its combat applications.

Weapons

Aikido also incorporates weapons systems including:

- The Jo (staff) which is a roughly a shoulder-height stick whose techniques were developed by Aikido’s founder to blend smoothly with Aikido’s core principles;

- The Bokken (sword) which stretches the core principles somewhat (due to its fatal cutting action) but can also have a lot in common with the empty handed system;

- And the Tanto (knife) which is mainly used for practising defence against knife attacks, and those defences fit in quite smoothly with Aikido’s core empty-handed system.

Borrowed strikes from Karate, Wing Chun, etc

Aikido classes sometimes incorporate common Karate strikes (front kicks, lunge punches, etc) to supplement a lack of aggressive striking techniques due to the system’s origins in Jujutsu which focuses on grappling.

Karate strikes were originally used to assimilate common attacks to defend from, but later became a part of the system in many schools.

These strikes don’t seem to fit in with the core principles of Aikido, especially if applied in the same way as they would be applied in classical Karate, for example to generate a significant impact or inflict significant injury, as opposed to manipulating the opponent’s bodily mechanics smoothly and efficiently which can only be done when the technique matches their posture and momentum, and is best done with Aikido’s native open-handed (palm and knifehand) techniques.

In recent years, Aikido classes outside of Japan sometimes seem to be borrowing strike techniques from the Chinese art of Wing Chun Kung Fu, such as the Jic Kuen (straight punch) often with simultaneous block (eg Tan Da) because they seem to fit in well with the Aikido system and help to fill the gap where Aikido lacks aggressive closed-fist striking techniques for tackling sticky close-quarter situations. What we don’t see though, is the incorporation of the softest, most balanced, least aggressive, most defence-oriented form of Wing Chun, which perfectly complements the core principles of Aikido (and Tai Chi) but is extremely rare to find even in Wing Chun clubs.

Philosophy

Aikido was created by Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969) to be a non-aggressive system of self defence — not for preemptive or aggressive assault, and certainly not hot-headed.

In this respect, Aikido is in principle very similar to Chinese Tai Chi, and is the polar opposite of the Israeli military training system of Krav Maga and the modern combat sport of MMA which are both unrefined (lacking finesse), aggressive (brutalistic) and somewhat discourteous (even sociopathic) by nature.

Aikido is a pacifist (anti violent) system of martial art that provides good full-body exercise — even more well rounded than Tai Chi in some ways due to its integration of plenty of rolling and kneeling, although it lacks depth of squared-up small-frame skill such as that which is abundant in Wing Chun‘s Chi Sau (Sticky Hands) exercise and can also be obtained somewhat from Tai Chi’s Tui Shou (Push Hands) exercise for example.

Aikido emphasises efficient use of body mechanics to smoothly pacify an opponent with minimal effort, to conserve energy and inflict minimal injury on the opponent. It is a wholly defence-oriented martial art, for those who are against violence. It’s easy to shoot someone for bad-mouthing you, but Aikido is all about increasing your skill, to increase your control of the situation, to increase your confidence and increase your self control, so that you can tolerate more of an assault before feeling fear and reacting, and so that when you react you only do so as far as is necessary to effectively defend yourself, rather than over-reacting and unnecessarily injuring the opponent or escalating the situation. This is what you like if you’re a peace-seeking person with love in your heart, even for your brother who attacks you. This compassionate approach is easy to shun — it takes real confidence in your ability to adopt this behaviour — this is what many a devout Aikidoka (Aikido practitioner) trains for. We believe that we don’t need to learn how to be angry, we need to tame our anger and learn how to keep cool under pressure in the interest of giving the most peaceful outcome the best chance of happening.

Aside from its anti-grappling techniques, Aikido is also a great art for helping you to master balance, mobility and finesse — both as an individual and during a physical struggle with other people.

Aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was also a deeply spiritual man, committed to studying the philosophy of war and peace, and to helping his righteous followers develop a graceful character. People may wish to learn martial art in a desperate bid to effectively exercises their right to defend themselves — if they refine their movement and mentality from gross or haphazard to become graceful then they’ve achieved something great.

Aikido vs Jujutsu & Judo

Aikido’s moves originate from Jujutsu (aka Jiu-Jitsu) — the Japanese art of technical grappling (as opposed to brute force grappling like Sumo wrestling), crossed with swordsmanship (Kendo/Kenjutsu). As such, there’s lots of arm-lock based throws and takedowns (a trademark of Jujutsu) and a lot of large-frame movement (borrowed from sword technique).

More so than with modern-day Judo and Jujutsu, Aikido embodies finesse.

- Jujutsu was the original Japanese art of technical grappling which included all the moves — the good the bad and the ugly. Aikido just utilises the good & pretty.

- Judo was then drawn from Jujitsu, taking a select set of moves to focus on, for practicality and ease of training; but not so much for minimisation of damage to the opponent, energy conservation or free-flowing ‘Ki’ (energy/spirit) as per with Ai ‘Ki’ Do.

Aikido vs Tai Chi

Aikido’s devotion to using minimal effort for maximum reward, while avoiding any unnecessary conflict or damage to oneself or ones adversaries, makes it in principle pretty much identical to the Chinese Kung Fu system of Tai Ji Quan (Tai Chi Chuan). Beside the core philosophy, Aikido and Tai Chi in practical terms both usually emphasise ‘large frame’ techniques (due to the root of swordwork, and lack of strike skill in Aikido due to its other root of jujutsu; and due to the Tai Chi tradition of teaching small-frame (close-range fighting) only behind closed doors, and big frame to everyone else for its health benefits and non proliferation of violence in society at large — those closed door secrets became very much lost in time, and are now more apparent in arts like Wing Chun Chi Sau (sticky hands) which evolved from Tai Ji Tui Shou (push hands) a few hundred years ago).

As for the key differences between Aikido and Tai Chi — they are how Aikido emphasises grappling, and has a lot of rolling around on the floor. Tai Chi on the other hand is very much a stand-up art with a more even balance of striking/blocking vs pushing/pulling.

Steven Seagal — Aikido 7th Dan

Steven Seagal, the straight-to-DVD action movie star, is famous for his martial arts movies but also famous within the real-life martial arts arena as being a genuine “7th Dan” Aikido master, which is pretty high considering the well-regulated upper-echelons of the world’s Aikido community to this day. Just to put this grade into perspective, there’s the odd 8th Dan teacher in the UK and a few leading western countries, and there’s a handful of 7th Dans in the UK — especially in Birmingham — but Greater Manchester has merely a couple of 5th Dan teachers, one 6th Dan and a retired 7th Dan as detailed in our guide to Manchester’s various Aikido classes, linked below. Even Japan’s Hombu Dojo itself boasts only half a dozen instructors graded higher than 7th Dan.

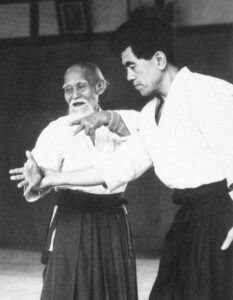

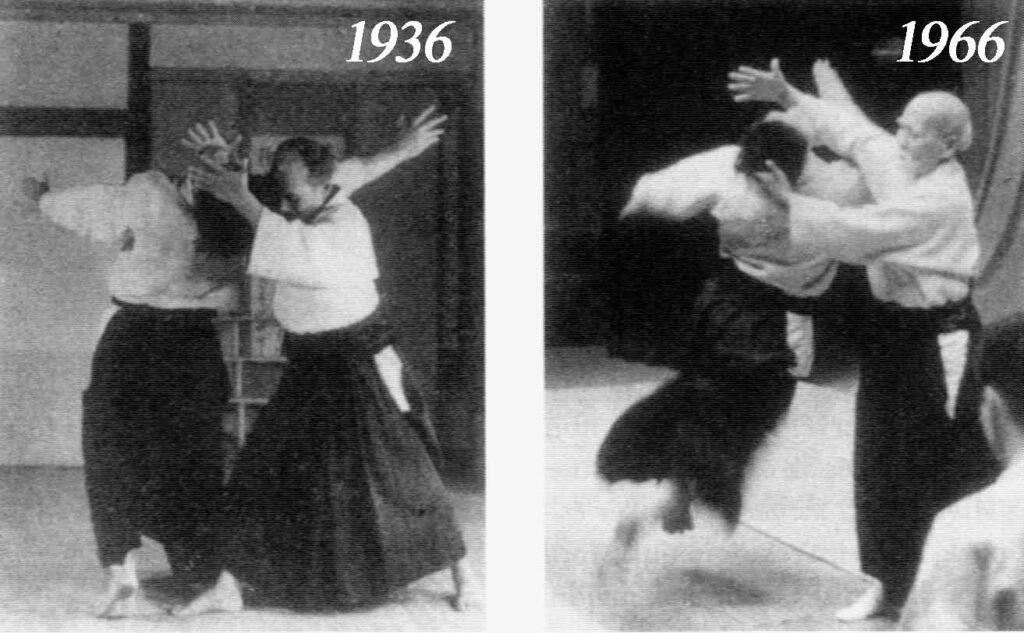

In this video (below) you can see a few common empty-handed Aikido moves demonstrated very much like how they’re practised all round the world today; followed by some weapon moves. Then Seagal joins the demo like a bandana-wearing pirate and demonstrates his style of Aikido which is more direct & aggressive, with a contemptously casual posture and hand techniques that resemble the more brutal side of Jujutsu which Aikido was intended to disassociate itself from. Both styles are less delicate than the way Ueshiba (Aikido’s founder) practised in his later years (as can be seen in the video further down the page).

Typical class content

In day to day classes, as a beginner you can expect to be practising lots of wrist grab defences, half-way arm-locks into throws and full-way arm-locks, as well as lots of forward rolling and backward rolling. There will also be some work from seated-kneeling (‘seiza’) positions. Plus a little Karate-style corkscrew punching and kicking, and some weapons work when you get to a certain level — both inherited as standard from Japanese martial culture.

As you progress and the main moves become familiar to you, you’ll learn variations of them until you have a well-rounded moveset to draw from. Then you’ll be ready to defend from free-flowing random attacks — initially 1-on-1, then many-on-one. These attacks are usually staged, or at least made easy for you to defend from — they involve people trying to grab your wrist and not letting go — there’s no serious punches thrown, and no switching of grip by the attacker — this is all to help the student learn the basics and master the art of defending themselves from a very one-dimensional assault.

How practical is this?

The persistent practice of defending from heavily telegraphed, totally one-dimensional attacks may be a very useful, practical training method for bulk teaching of fundamentals to beginners, who from a pacifist’s point of view, should be taught to be graceful in a fight, not aggressive, for the best chance of long-term survival in most situations. For example, if we were to teach a beginner to punch first and ask questions later, what if their opponent then drew a knife? Or are we teaching the beginner to kill first and ask questions later? Maybe we should reflect on our definition of practicality if this is the case.

Still, many people, especially in the MMA arena, see Aikido training as inefficient for refining the practical skills of an advanced martial artist. Many would go as far as to say the moves are simply impractical. Many people speak of Aikido as having a lack of ‘pressure testing’ but if we look back to the life of its founder, Ueshiba — he was challenged by (and defeated) many martial artists including army generals and sumo wrestlers who became his students immediately thereafter. Obviously he had a level of skill and confidence that enabled him to accept those challenges, and that doesn’t mean the average Aikido instructor is qualified to or should feel any duty to do the same. But it was something Ueshiba himself was both capable of doing and felt a need to do — perhaps to spread a message of softness among certain hard-nosed fighting communities, or to simply build a reputation and earn a living. This is why, many people in Aikido say if you fail to find practicality in your Aikido it is a flaw of yourself (and/or your teacher) but not a flaw of the system itself — you just have a lot more to learn about true Aikido.

Nevertheless, if you do get as far as mastering what Aikido offers under any highly graded teacher, you will surely then have a strong foundation of balance, coordination and sensitivity within contact scenarios from which to continue your self-development as an outstanding free-thinking martial artist thereafte. Plus you can of course also reap all the same physical and mental health benefits of practising smooth, full-body movements that a Tai Chi practitioner or Yogi would obtain from practising their arts in the mean time.

This video gives you a chance to see Aikido’s founder in motion — observe his lighthearted yet serious demeanour. Can you appreciate the delicate genius in his techniques, while also acknowledging how one-dimensional, non-resisting and respectfully compliant his ‘attackers’ are?

Traditional etiquette vs practicality

Aikido retains most of its original technicality — party because it’s a fairly new style, being less than 100 years old, which means that ‘fraudulent’ or unrefined teachers haven’t yet so much infiltrated the higher ranks of the art and broadly commercialised it — and partly because it was founded by a master of Jujutsu who was capable of establishing a thorough routine of training and promotion, centralised by the founder’s own son and grandson to this day in the Hombu Dojo, in Japan. There are of course plenty of ‘self-defence oriented masters of Aikido’ who teach moves that don’t resemble what gets taught in the Hombu Dojo, but if you seek the traditional style, it’s still pretty easy to find a high level of authenticity in Manchester, the UK and most of the developed world.

On the down side (there’s always a down side in mass martial arts) — Aikido’s ability to successfully retain its technical qualities is largely due to how it’s consistently bogged down in tradition Japanese etiquette from school to school — this of course limits its practicality for street self-defence because the student is forbidden from really ‘pressure testing’ the teacher’s moves or asking too many questions. We’re therefore limited to what can be learnt without behaving brashly or without unwelcomed intuition in the dojo. Much like in a traditional Karate class, only the teachers and their closest assistants are permitted to throw their weight around, and this of course grants the teachers access to make things up without being interrogated for it. Of course not all clubs are the same, but this is the trend that helps to preserve Ueshiba’s original methods down the generations. This level of traditional courtesy also serves another legitimate purpose — it helps to ensure a certain level of discipline in all students, for the safety of all who participate in the classroom environment, and it gives the teacher authority to teach how they see fit, without being distracted when they don’t wish to be. It really puts the ball in the teacher’s hand. But wouldn’t a confident teacher then give the ball back to the paying student, at least occasionally? In a private lesson, maybe, but in a busy dojo the teacher may need to be more systemised to ensure value is spread fairly between all students in attendance.

Aikido Classes in Manchester

Aikido is a very popular martial art in the UK and there’s plenty of options in Manchester as one of the country’s biggest and most culturally diverse cities. If you’re interested in finding Aikido classes in Central or Greater Manchester, check out this page which provides a rundown of all the top teachers and all their class times and locations that we know of. Also featuring travel advice in case you’re looking to travel from the city centre to these classes by foot or rail:

Aikido is a very popular martial art in the UK and there’s plenty of options in Manchester as one of the country’s biggest and most culturally diverse cities. If you’re interested in finding Aikido classes in Central or Greater Manchester, check out this page which provides a rundown of all the top teachers and all their class times and locations that we know of. Also featuring travel advice in case you’re looking to travel from the city centre to these classes by foot or rail: